A Peculiar Survey

Back to updatesThe following post you are about to read is a lengthy but necessary one. Generally, at The Ocean Cleanup, we avoid speaking out against criticism. We welcome all thoughtful critique and value the insight, but recently we experienced something different.

At The Ocean Cleanup our mission is to rid the world’s oceans of plastic. Our first target is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the largest accumulation of floating trash in the world, containing 1.8 trillion toxic pieces of plastic.

Once captured by the currents of one of the five ocean garbage patches, the plastic persist, meaning the garbage can continue to do damage for decades or even centuries to come. On top of that, the plastic will become more harmful over time. Sunlight weakens plastic, causing it to fragment into ever smaller pieces, which are small enough to be ingested and thereby pose a hazard for the food web that includes us humans. Furthermore, 46% of the plastic by weight comprises discarded fishing nets and lines which are particularly hazardous to marine life.

While the need for a cleanup is clear, the engineering behind developing an efficient system that can survive at sea for decades is hard. It took years for our skilled team, which currently consists of scientists and engineers with around 400 years of offshore engineering experience between them, to develop the technology. After 273 scale model tests, six at-sea prototypes, mapping the patch with 30 vessels and an airplane, and going through several technology iterations, we are now ready to put the first ocean cleanup system to the test, launching from San Francisco on September 8th.

This doesn’t mean we know everything. We’re confident we’ve eliminated risks where possible, but not everything can be calculated, simulated or tested at scale. The only way to be sure is to trial it at full scale. Our first system should be regarded as a beta system, allowing us to eliminate the last remaining uncertainties before scaling up.

Nonetheless, since we’re doing something very new, we expect critics to challenge our work and rightly so. Pretty much every new technology in history has been the subject of skepticism with greater and lesser justification. According to past critics, airplanes would never fly, there would be no demand for PCs, electricity would kill us all and the speed of trains would damage our brains. Valid criticism helps to inform the development of new technology and to keep us sharp.

While I believe it is always good to be skeptical (realizing we don’t know everything, we actively welcome it), it goes a step too far when critics risk deceiving the public to prove that their viewpoint is right.

A recent spate of criticism appears to stem from a blog on a website called Southern Fried Science, written by David Shiffman. The core of his piece is an argument from authority; ‘experts’ do not think cleaning plastic from the ocean is a good idea, according to a survey he conducted. This survey has been frequently cited in the media this week (including The Telegraph, Business Insider and Stuff.co.nz).

The referred blog appears to have achieved an impressive conclusion, but once we zoom in on the details it becomes clear that 1) the survey is too biased to draw any scientifically based conclusions from it, and 2) Shiffman employed misleading tactics to ensure the results matched his opinion (including framing questions in extreme contexts, misquoting our responses to weaken the validity of their response).

AN UNUSUAL INTERACTION

On May 18th, 2018, our Lead Oceanographer received an email from a researcher who had received an invitation from Shiffman to fill out a survey about The Ocean Cleanup. The tone and text of the invitation to participate in the survey had aroused the researcher, suggesting a bias that negative comments on The Ocean Cleanup project were invited, leading to sharing these concerns with our colleague.

Caring about addressing any and all concerns, either to provide reassurance or to implement further improvements in our plans, our COO Lonneke Holierhoek reached out to him on the same day, expressing an interest in discussing his quest for opinions and offering input at source.

Almost two weeks went by without any response to Lonneke’s email until, on May 28 at 6:14pm (just after office hours) Shiffman sent Lonneke an email in which he stated: “I was about to contact someone from your organization.” This was followed by four lines of broad statements of critique, closing with a warning:

“I’m publishing the story tomorrow morning (Pacific time), so please send a response promptly if you’d like to have it included. Otherwise I’ll have to include the statement that “a representative from the Ocean Cleanup did not respond to a request for comment as of publication time.”

Lonneke replied, offering a phone conversation to understand the details behind the listed concerns, and requested the list of questions asked. After several attempts, Shiffman accepted to have a phone call only after we offered him the following statement as an alternative:

“When asked to engage in a conversation to deepen out these concerns and enabling The Ocean Cleanup to respond to facts, rather than broad statements, unfortunately he did not offer us that opportunity. As The Ocean Cleanup has stated many times: we welcome constructive criticism, because it helps us to improve our approach. The information Dr Shiffman was willing to share with us, lacked sufficient depth however to provide a well-founded response.”

We never received the questions, meaning Lonneke was still forced to provide rather general responses. To make matters worse, Shiffman juxtaposed these general defenses with specific comments of the respondents, giving the impression that Lonneke was dodging these unknown questions. At the end of our interaction with Shiffman, upon his explicit request we offered him a formal statement on the interaction to include in his blog. He decided not to publish it.

THE SURVEY

But what about the survey itself?

There are many thousands of people knowledgeable on the problem of plastic pollution worldwide. David Shiffman selected 51 of these through his own network. Of this small subset, only 15 of these decided to reply to his invitation. In this invitation to participate, the survey was framed as follows:

“I’m asking about the Ocean Cleanup project, the large object designed to remove plastic from the ocean. I am trying to get a sense of the state of expert opinion on this topic. My impression from talking to colleagues is that there is a great deal of expert skepticism, but that this never shows up in often-uncritical media coverage.”

71% of recipients decided to not engage based on this invitation.

In science and journalism, one carefully forms the sample group and designs the survey to eliminate biases, ensuring the conclusion has any value. In this case, no such attempt appears to have been made.

The resulting response bias is evident from the answers to Shiffman’s survey questions. To the question “If The Ocean Cleanup can actually remove plastic pieces that are >1 cm, is that helpful?”, an incredible 80% of his respondents said “no”.

Considering the framing of Shiffman’s survey invite, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that his questions suffer from framing effects as well. See the following question as an example:

From this, Shiffman concludes that “Not one surveyed expert believed that the Ocean Cleanup’s approach (attempting to remove plastic once it’s already in the ocean) is the best solution.” This ignores the fact that The Ocean Cleanup has always advocated a two-pronged approach of both prevention and cleanup. Dealing with the legacy plastic is just one half of the solution.

Elsewhere the article concludes that most plastic is small and thus cannot be removed from the oceans. Lonneke had referred Shiffman to the results of our extensive mapping work of the patch, which was published in Nature Scientific Reports earlier this year and demonstrated that 92% of the mass of plastic in the patch is large plastic. In response, Shiffman wrote: “note that this study was funded by the Ocean Cleanup and includes Ocean Cleanup staff as coauthors).” Shiffman’s insinuation ignores the fact that this data, unlike his own, comes from a peer-reviewed scientific publication, produced by an international team of scientists affiliated with six universities.

WHAT THE DATA SAYS

In Shiffman’s blog, three main points of critique are voiced: 1) the environmental impact, 2) the size and depth of the plastic make a cleanup impractical and 3) it’s an expensive approach. Here I’ll briefly address them:

Environmental Impact

The number one reason we’re developing ocean cleanup technology is to stop the destruction plastic is causing to hundreds of species worldwide. Making sure our systems effectively catch plastic while not negatively impacting (marine) life is, therefore, our number one design driver.

After we completed the design of the first cleanup system, we contracted the independent environmental consultancy company CSA Ocean Sciences to conduct a voluntary Environmental Impact Assessment. The full study was published recently and can be read here. Although it is very hard to assess the impact of something that has never been done before, no high risks were identified.

Our ocean cleanup systems are designed to be inherently safe for marine life, because the systems move through the water very slowly, powered by wind and waves. They don’t use nets but non-permeable screens (making entanglement impossible) and the plastic is only extracted from the water periodically in a way which minimizes the risk to marine life, further mitigated by the presence of trained personnel to check before lifting the plastic out of the water.

Having said that, we continue to follow a precautionary approach; in parallel to testing the cleanup technology using System 001, professional (independent) observers will conduct an environmental monitoring program to study the interaction between the system and marine life.

Size and depth of the plastic

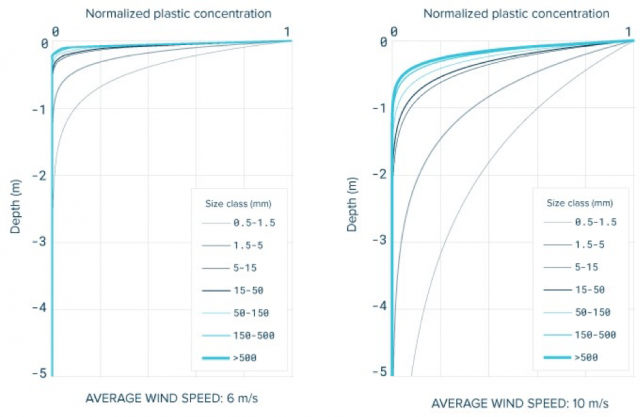

In 2014 and 2015 The Ocean Cleanup organized several expeditions to measure the vertical distribution of plastic in high resolution for the top five meters of the ocean. Results were published in Biogeosciences and Nature Scientific Reports.

The smaller pieces become, the more sensitive they are to mixing from wind and wave turbulence. The measurements showed that even the microplastics stay on or near the surface in turbulent seas. The highest concentrations of microplastics were found directly on the surface, and quickly went to trace concentrations at only a few meters depth. Larger objects, which comprise most of the mass of plastic in the ocean, are more buoyant, and are found almost directly at the ocean surface.

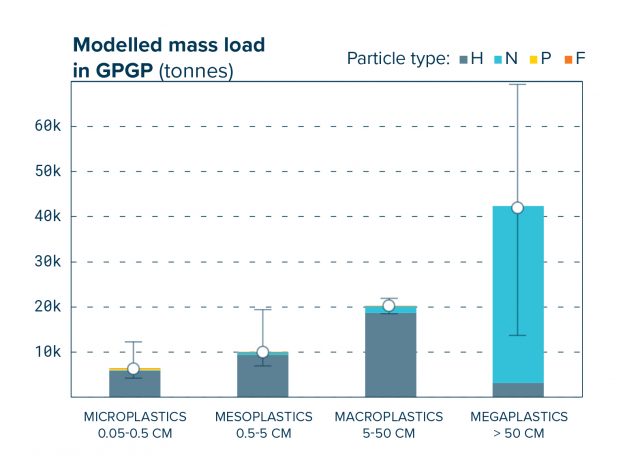

With regards to particle size, it is commonly said that most plastic is too small to be cleaned up. Although microplastics are most abundant by count, the reconnaissance of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch revealed that 92% of the plastics are large objects when looking at their mass. The smallest size class we quantified, pieces smaller than 1.5mm, accounts for just 0.77% of the mass.

Compare it to standing next to Mount Everest while holding a handful of pebbles. While the pebbles are more abundant by count than the mountain (for which the count = 1), obviously the mountain contains more rock. It’s the mass that counts.

Based on computer modeling and scale model tests we predict the capture threshold of our cleanup system to be in the millimeter range, meaning the vast majority of the plastic is expected to be recoverable. However, in the coming decades, this large debris will fragment into microplastics, which is why we must clean it up now – before it is too late to be able to retrieve them.

Cleanup Cost

Of course, it’s going to cost money to clean up the ocean garbage patches. But when we consider hundreds of species are at risk because of plastic pollution and the potential health effects of humans consuming contaminated seafood, ridding the oceans of plastic is surely worth a small part of our resources.

And surprisingly, cleaning up the ocean garbage patches looks to be a lot cheaper than most people expect. Compare it to garbage collection and disposal in New York City, which has been quoted to cost US$ 2.3 billion per year. We expect the North Pacific cleanup fleet to cost several tens of millions of USD per year, including depreciation of the hardware and the cost of shipping it to port. To put that in perspective: cleaning up an oceanic area twice the size of Texas is expected to cost about 2% of that of a single city.

Compare this to the US$ 13 billion the ocean plastic pollution is estimated to cost in damages to industries around the world, and it becomes imaginable that cleaning up is far cheaper than leaving the plastic in the oceans.

IN CONCLUSION

Cleaning up the ocean garbage patches is hard, and there are still plenty of things we don’t know yet. As with any high risk/high reward technology project, it’s likely we’ll be encountering many more setbacks along the way.

We can thus use all the help we can, which includes welcoming constructive feedback to help challenge our work.

However, criticism is much more valuable, both for us and the public, when based on factual data rather than on a biased set of opinions.